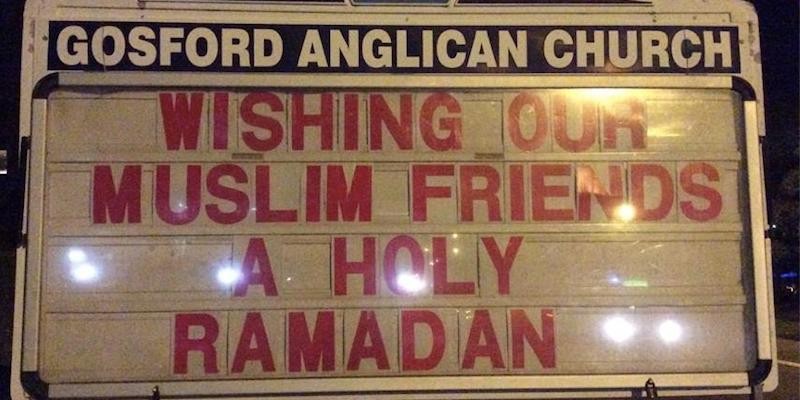

Ah, Gosford. You were a distant memory tucked away in the back of my mind until Elite Daily brought you back to life this week. What appears to be just a brief blog post shouting out a Christian church for being, you know, Christian and extending well wishes to Islamic passersby commencing Ramadan means so much more to me.

My family moved to Gosford in 1989. My sister Julie had a mysterious cough (which she still has to this day, SMH) and thinking it was due to us living on Parramatta Road, Sydney’s most clogged thoroughfare, Mum pulled us from the chaos of the inner city to the beautiful beaches of the Central Coast, joining my aunty and cousins who’d relocated months earlier. A different world, indeed.

In Summer Hill, my friendship group was a rainbow coalition: Indian-Fijian, Filipino, Lebanese, Maori. Thanks to gentrification in 2015 it’s a predominantly white area now but back then you name it, we had it. I don’t know how I knew at eight years old Gosford would be an extremely different environment for me, but I did. And it was. I experienced racism for the first time there and it was so stinging and immediate I’ll never forget how blindsided I was by it.

As soon as we moved Mum enrolled Julie and I at St. Patrick’s, East Gosford. We’d gone to St. Patrick’s in our old neighborhood so we thought we’d ease right in. How wrong we were. From the moment I started third grade (or Year 3, as we say in Australia) I knew I was different. There was only one other “ethnic” girl named Aphrodite (she was Greek Cypriot) and instead of embracing me, she stayed away like the plague. She ignored my smiles and acted as if she couldn’t understand me when I’d strike up conversation. I remember she had gorgeous thick, black curly hair and wore it in a bun every day for fear of standing out from the limp, mousey brown strands surrounding her. The other girls called her “Dede” and I thought she was a sellout.

It wasn’t too long before I was called “wog” by the other girls. I’d heard the word vaguely before, but never directed at me. I was heated. Who the hell were they to speak to me like that? Just as I reported back to Mum I was going to have to lay hands on these racist little bitches, Julie came home from her kindergarten class one day to let us know, at the tender age of five, another student laughed in her face and told her that her beautiful dark brown eyes looked like “poo.” She cried as she shared they constantly teased her friend Michelle, the only Aboriginal girl in class. Being the protective sister I always was, I remember feeling angry and helpless. My campus was separate from my very shy little sister’s and the thought of not being able to protect her killed me. My social conscience was highly developed from a very young age and therefore I expressed myself in the only ways a child knows how: with my temper and fists. We eventually decided to move back to the city because, frankly, we missed “us” (our neighbor coming over and observing my grandmother frying kibbe on the stove with an “Ewwwww, what is that? Looks disgusting!” was probably the final straw). We missed feeling accepted and part of a community. I slipped right back into my old school, with old friends who looked and talked just like me. Those two years away felt like a bad dream and still do to this day.

Gosford, it appears, is a very different place nowadays. For an Anglican church to post a sign acknowledging their Muslim neighbors in a community that used to frown on diversity makes my heart burst. In these times when racism is viewed as a dirty word (but its results are not) you cannot help to be encouraged by small steps towards righting the wrongs of the past. That’s why we should never refuse to take notice of the pain felt by those who came before us simply because things [might have] changed in the present. And that’s why what appears as a plain sign to you means the world to me.